Sound and Vision is a weekly segment on The Breakfast Spread exploring films and soundtracks with Xan Coppinger. With an equal love for armchair criticism, music, sound design, and film studies, Xan takes listeners on a 30 minute trip through cult-classics, memorable soundtracks, current film news, and a diverse range of cinematic topics. PBS is pleased to present Sound and Vision's monthly feature article, where Xan will be diving deep into current topics and analysis in film.

Cyborgs and Feminism in Film:

The Life and Works of Lynn Hershman-Leeson

“I’ve just felt invisible my entire life. Babbage saw the beginnings of what I was, but nobody has actually seen me.”

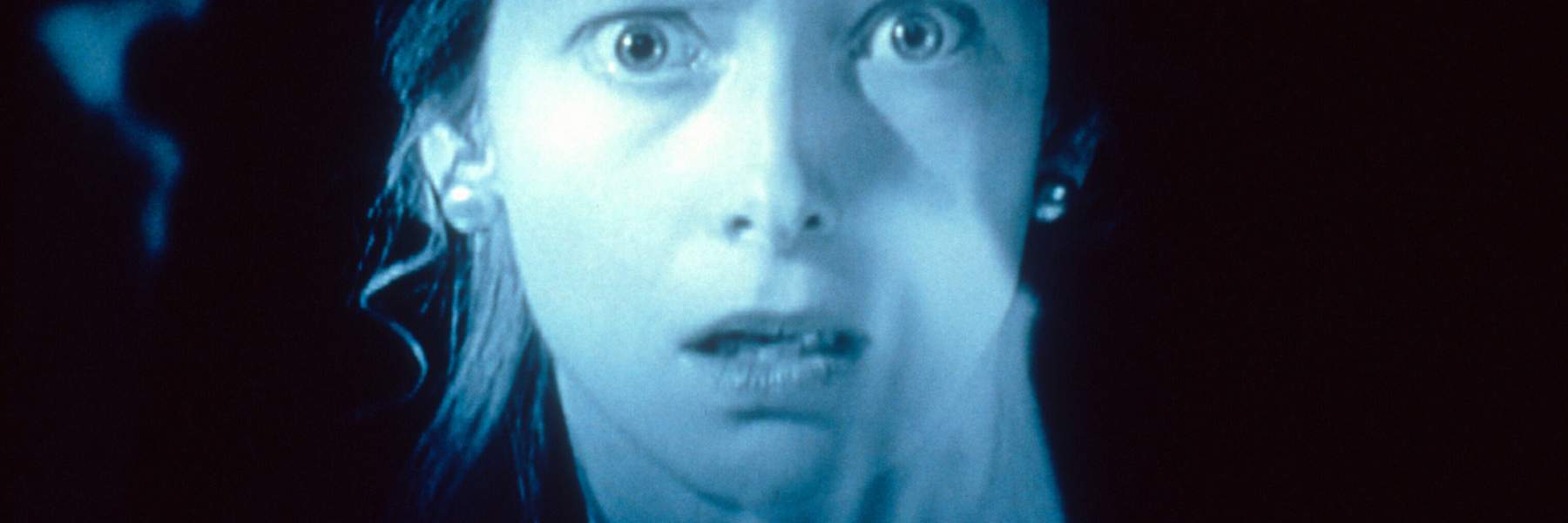

This is Tilda Swinton strewn, sweating and delirious, across her bed in 19th century England. Cutting rhythmically between shots of her unconscious body, soundtracked by pulses of laboured breathing and the eerie musical work of artist collective The Residents, Swinton delivers her final monologue for Conceiving Ada (1997).

“Because I never became.

I never really was, what I should have been.

I don’t know how my children even came out of me. They’re not what I wanted to come out of me.”

Ada as a character is a homage to Augusta Ada King, Countess of Lovelace, the first computer programmer in history. Child of romantic poet Lord Byron -

“Man’s love is of man’s life a part; it is a woman’s whole existence”

(not very romantic, is it?)

Ada worked on Charles Babbage’s Analytical Engine before her life was taken prematurely by uterine cancer at the age of 37. An often overlooked pioneer in computer science, her disappearance into the shadows of history highlights the place women were traditionally given (i.e no place) in mathematics and science. In Conceiving Ada, artist and director Lynn Hershman-Leeson delivers a historical representation of this visionary woman while incorporating Ada, as a fictional character, into her wider cyborg-sci-fi universe spanning both film, art, and personal performance.

In film and historical accounts, Ada is portrayed as being notorious for mixing her career with sexual escapades, supposedly wooing countless mathematicians and authors to ‘further her education’. However, as neither Wikipedia nor Hershman-Leeson are privy to Ada’s intentions, her mixing of flirtation and mathematics depicted solely as a career move is perhaps just denying the often overlooked eroticism of numbers; it certainly speaks monuments about how continuously shocking it is to discover women have both careers and a sexuality.

Ada is paralleled by Hershman-Leeson against the modern-day computer whiz Emmy Coer (Francesca Faridany). In alternating scenes we see the timeless struggle of oppressive mothers; lovers who meddle, out of jealousy or emasculation, with their work; and experiences with patriarchal pressures to forgo a career for motherhood. Determined not to be sidelined into the shadows by the predetermined role they have been handed in society, both characters grapple at length with the notion that in order to exist as a woman they will be deprived, or forever running out, of time.

“Time is the only thing I ran out of. I didn’t run out of thinking and I didn’t run out of the energy.”

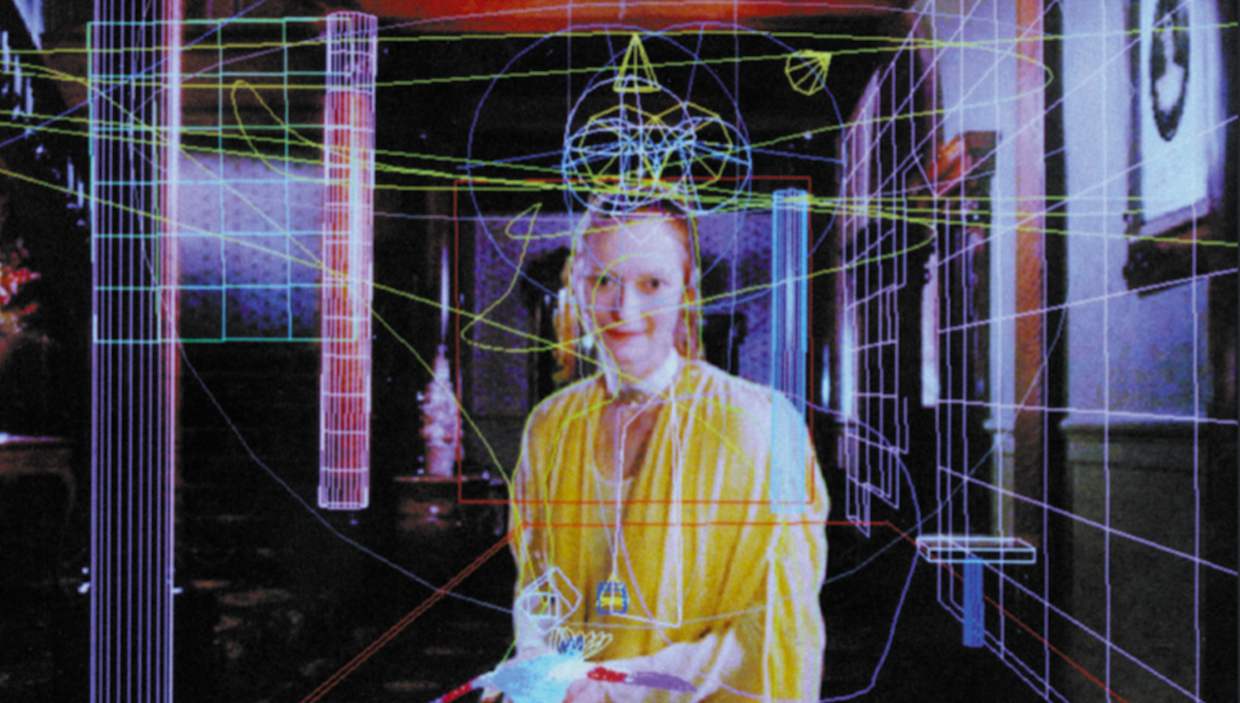

This stark comparison of two women, separated by hundreds of years but in seemingly unchanging social circumstances, is a glimpse into a much wider vision that Hershman-Leeson has spent her life cultivating. In her following film, Teknolust (2002), Tilda Swinton returns to play four parallel characters living in a world where sex is no longer required for reproduction and women are, finally, able to pursue their own adventures. This is in itself a reference to Hershman-Leeson’s own performative art project, Roberta Breitmore (1974).

Almost a decade long, this work had Hershman-Leeson explore concepts of time, fragmentation, and gender identity using her own body as performance. With use of costumes, cosmetics, and a signature blonde wig, Hershman-Leeson’s performance was far more than just acting; Roberta Breitmore’s identity was verified by rental certificates, employment letters, drivers licenses, credit cards and dental records. Her participation in the world was heavily documented and eventually began to disseminate into multiple hired actors all performing Roberta.

Hershman-Leeson and her three actors wore identical wigs and costumes, went on meticulously recorded dates with strangers found in newspaper-callouts from Hershman-Leeson, and eventually resulted in the 1978 work ‘Lynn Herhman Is Not Roberta Breitmore / Roberta Breitmore is Not Lynn-Hershman.

This piece, a lookalike contest to find the ultimate Roberta, was a performative way for Hershman-Leeson to finally disseminate and fracture her visionary character. The magnum opus of this work however, is the final performance set in a Renaissance palace in Italy, where Roberta was officially exorcised and henceforth disappeared from the public domain.

It is believed that Hershman-Leeson is heavily referencing this performative work in Teknolust, where Tilda Swinton’s character is fractured into four women and the line between cyborg and human is increasingly blurred. Tilda is Roberta, Roberta is Hershman-Leeson, and Hershman-Leeson is herself part of a much wider conversation between gender, cyborgs, and the female form.

The films Teknolust and Conceiving Ada certainly rely more on conceptual genius than cinematic prowess, with critics noting these films were either ‘Tilda Swinton saving an otherwise pointless 90 minutes’ (Fandango, October 9, 1997), or a sci-fi ‘dud’ weighed down by ‘woodiness and shrill didacticism’ (Cranky Critic Movie Reviews 2020 / New York Times 1999) [woodiness being such an exotic insult for a film that I’m not entirely sure it’s even negative].

Indeed, these films aren’t fleshed out by great acting or smooth cinematography; the pleasure is in being able to observe a snippet of the conceptual feminist-sci-fi universe they are woven into. Hershman-Leeson went so far as to structure and shoot every scene ‘using a DNA image as a model for the actor’s placement and camera movement’. If that’s not a worthy excuse for clunky cinematography I’m not sure what B-grade films will ever do.

To add to the sci-fi madness, Hershman-Leeson then went all-out and had touted LSD scientist Timothy Leary play a mentor stuck in a computer screen. Learly was in fact dying of prostate cancer at the time and during this film had a website both monitoring his demise and discussing his plans to freeze his body in cryogenic suspension in order to live eternally in cyberspace. Unfortunately, while Emmy was able to execute this with Ada in Conceiving Ada, Leary’s execution of this in reality was somewhat muddled due to the financial expense of freezing an entire body. After downgrading the economic plan to purely head-freezing, Leary eventually settled for scattering his ashes in outer-space.

The soundtrack to Conceiving Ada is composed by appropriately enigmatic collective, The Residents. With over 60 albums to their name, all members of The Residents maintained complete anonymity during their career in order to channel all public attention into the content of their art. Resultingly, The Residents always performed silently with costumes and masks and their wikipedia page is weighed down heavily by conspiracy theories of their true identities (ten days before his death, Hardy Fox identified that indeed he, and not George Harrison of The Beatles, was the lead member of The Residents).

The Residents covered everything from true-crime podcasts, rock and roll, experimental, disco, chaotic theatre performances, talking blues, live history lessons in american music, performances exclusively devoted to Elvis Presely covers, computer games, ecclesiastical musicals, and a four-year long failed music video that never saw the light of day. It therefore seems fitting that a collective with such equally intense artistic visions was paired with the creative powers of Hershman-Leeson. Gender politics, cybernetics, and five versions of Tilda Swinton taking down the patriarchy; shout out to Hershmann-Leeson for inspiring feminists to keep breaking codes and social norms.

-Xan Coppinger

Xan Coppinger hosts the Sound and Vision segment on The Breakfast Spread each Tuesday at 8am, as well as co-hosting Solaris every Sunday at midnight alongside Clancy Balen. Keep your eye on pbsfm.org.au for more Sound and Vision feature articles on the first Monday of every month.